I’ve previously written about the violence that emanated from the Bull’s Head section of Scranton. Between the notorious actions of the Black Hand and the fact that the early Italian settlers were known to imbibe far too much alcohol on occasion, there was plenty of violence in this section of the then-booming blue-collar city.

And sometimes, that violence resulted in death followed by murder or manslaughter charges. One of the earliest recorded instances occurred in 1889 when a night of drinking turned deadly. I touched on this briefly in my “Black Hand Society of Bull’s Head” post. This post will go deeper into the fight that ended Antonio Pandolph’s life.

Party at Pandolpho’s

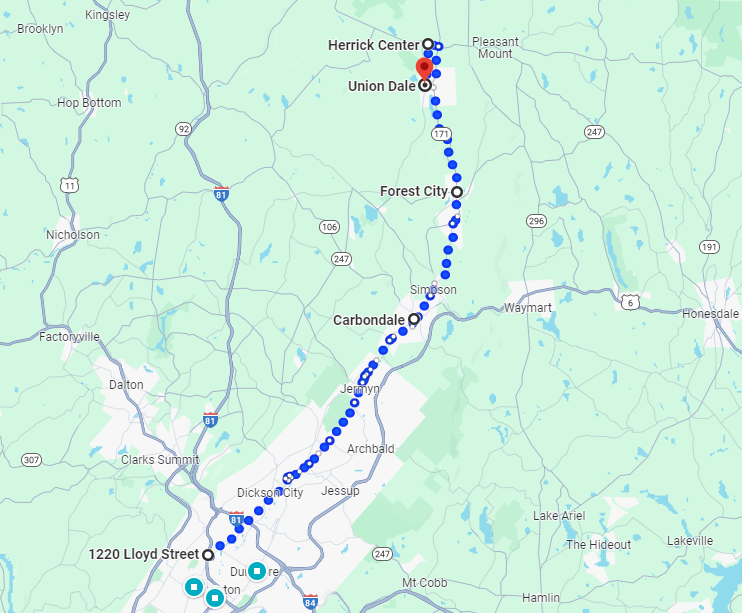

On the evening of March 9, 1889, several Italian men got together for a party. At around 8:30, they started drinking in Antonio Pandolpho’s (aka Antonio Pandolph) rooming house at 1220 Arch Street (now Lloyd Street) in Bull’s Head. The night was festive, with one of the men playing the accordion for entertainment and the other men singing and dancing the night away.

March 11, 1889

By about 11:00pm, they ran out of beer – so the partyers all chipped in for another keg – all except for one of the attendees, Carlo Grando, aka Carlo Grande.

Grando lived in the same boarding home as Pandolph. As Pandolph and the other men went to get another keg of beer, Grando threw out the old keg, an accompanying pan that collected beer, and some of the glasses that were used.

When the men returned at about 11:30pm, Pandolph noticed the missing items. He asked Grando who threw them out. Grando responded, “I did;” then Pandolph replied, “What did you do it for?” Grando shot back with something along the lines of, “I do as I please!”

Pandolph then approached Grando and the two men wrestled their way into the kitchen, with Pandolph telling Grando, “You better go home.”

When they emerged from the kitchen, a witness, John Mendicino, said Pandolph had blood on his neck. It was then that Grando shouted, “Anybody got a big enough heart, come on!” challenging anyone to try to detain him.

March 11, 1889

Mendicino went to restrain Grando, but others warned him to stay away. He was told “Don’t! You got nothing and he got a big knife!”

The men watched as Grando put away his knife and hurriedly left the home. Meanwhile, Pandolph lay on the floor bleeding from his neck – too weak to speak.

Dr. John O’Malley was summoned to the scene. When he arrived, Pandolph was still on the floor in the pool of blood, struggling to survive. The doctor would render aid that would spare his life – for now.

The Hunt for the Suspect

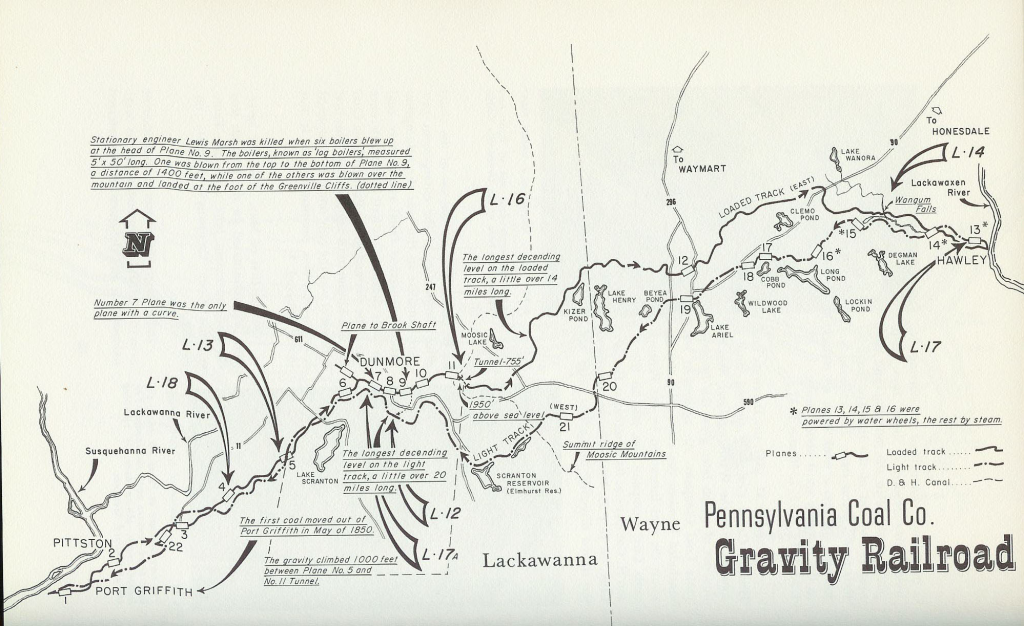

Police searched throughout the area but could not find their suspect. A wagon took the officers to Dunmore and on to Greenville (now Nay Aug) before returning to the city empty-handed. They set out again. This time they traveled to the Number 5 Plane of the Pennsylvania Coal Company’s Gravity Line that was near Palm and Blucher near East Mountain.

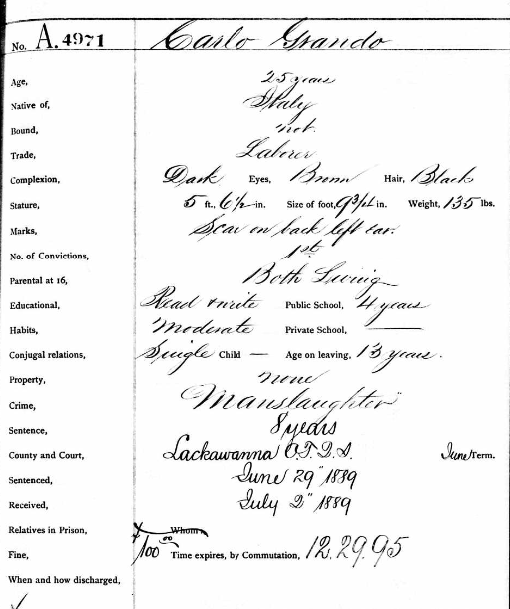

Along the way, they tried to interview several members of the Italian community, but the language barrier prohibited any real progress. At this point, Italian immigration to Scranton was still relatively limited. All they had was a basic description that Grando was “a young man, about five feet, eight inches tall, with dark hair and a smooth face.” A description that could match virtually any Italian.

Initial reports were that this was an “Italian vendetta” – that Grando had some history with Pandolph stemming from an earlier stabbing that occurred on a Green Ridge street car.

Assault Turned Deadly

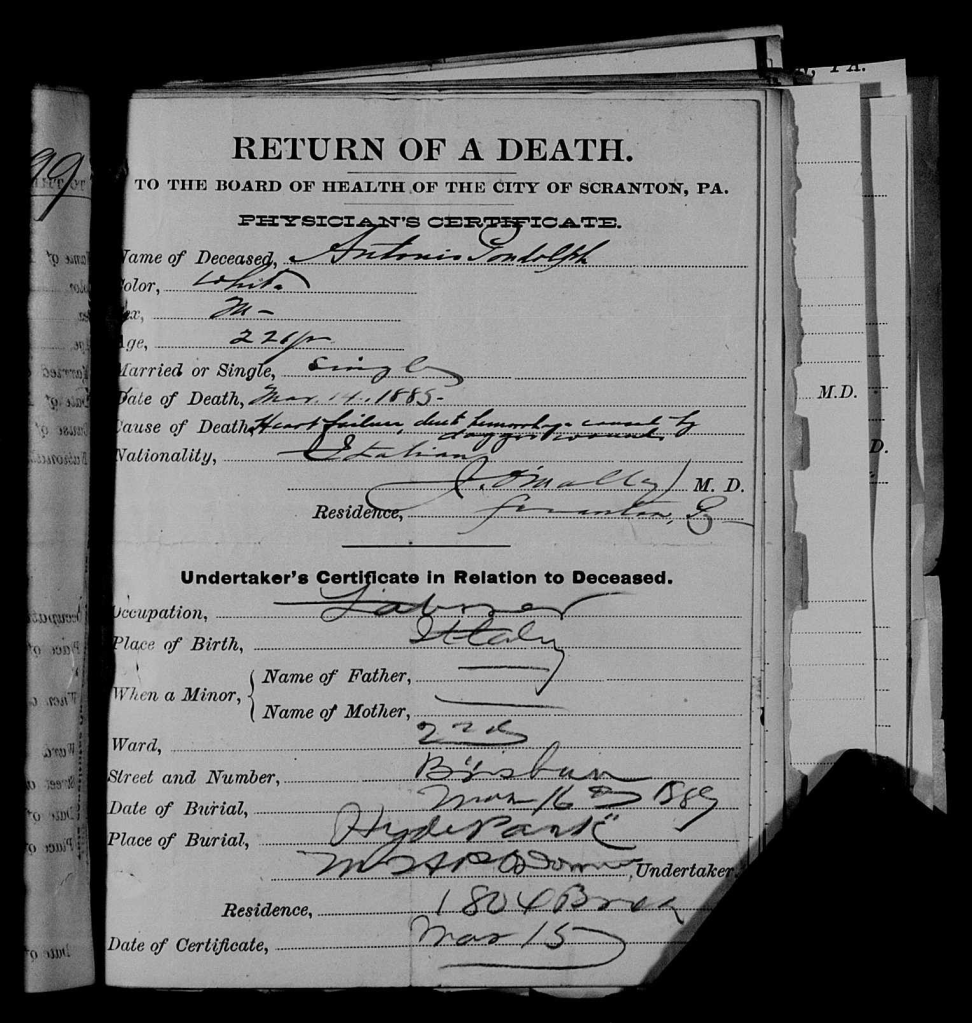

Days later, on the morning of March 14, 1889, what started as a minor dispute turned into murder. Antonio Pandolph, single, and at just 22 years old, finally succumbed to his wounds and was pronounced dead at 7:30am. He was laid to rest in the Cathedral Cemetary.

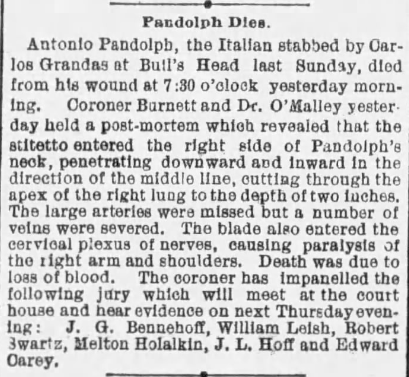

The gory details were outlined in the paper for all to read. Pandolph was stabbed by a large stiletto knife. The blade cut through his neck, severing nerves and causing severe bleeding. The coroner claimed that he ultimately died due to loss of blood.

March 15, 1889

Coroner’s Inquest

With Grande still on the run, the coroner’s inquest was held to see if charges should be filed. Several witnesses, under oath, corroborated the story – but none of them actually saw the stabbing since it occurred out of sight in the dark kitchen. The only man in the kitchen at the time of the stabbing was Francisco Pantano – but he did not show up for the inquest.

George Salvatore, a local cobbler, said he was at the party and said he saw Pandolph argue with Grando before the stabbing. He said Pandolph told Grando, “When you go to run my house you’d better go home.” Then, the two men grabbed each other before entering the kitchen.

Both Mendicino and Salvatore testified at the inquest that neither of the combatants seemed overly intoxicated. Mendicino added that he had known Pandolph for two or three years and never once saw him get into a fight. He knew Grando only a couple of weeks but added that some have said he was a “bad pill” when drunk.

Mendicino also testified that the day after the stabbing, while being attended by Dr. O’Malley, Pandolph said, “That fellow stabbed me for nothing.”

Also testifying at the inquest was Robert C Moore, a neighbor on Arch Street. Moore said he saw Grando throw the items out the back door of the home and when Pandolph came back, he said that Grando admitted he was responsible. He saw the men argue, then retreat to the kitchen. From there, his story lined up with the others. He saw Pandolph was bleeding and watched him fall to the floor.

The owners of the rooming house were Joseph and Ophelia Spott Rabitz/Ribitch/Reibich. They lived on the third floor of the building. Mrs. Reibich testified that she heard men talking loudly outside. She told her husband to stop it since it was Lent and it would give Catholics a bad name to “have such a time” during this solemn time of the year. She and her husband went down to the apartment below and that’s when Pandolph returned and questioned Grando.

Joseph Reibich added to his wife’s testimony. He said that he saw Grando after his scuffle with Pandolph. He held a stiletto knife in an aggressive position as he challenged others to restrain him. Reibich said the knife was approximately 12″-14″ long and had blood on it. Reibich also stated that Alessandro Mendicino (no relation to John) told him that he saw Grando take a knife out of his pocket and put it in his sleeve. When Mendicino questioned him, Grando replied, “You wait and see some fun after a while.”

A week later with Grando still missing, the inquest continued with new witnesses. Francisco Pantano, who was in the kitchen when Grando stabbed Pandolph, now testified that he didn’t actually see the stabbing, but when it was over, he saw Grando with a knife and heard Pandolph say, “My God, help me, Carlo Grando is killing me!”

Alessandro Mendicino was also there to testify. He added that he had seen the two men prior to the incident. He said a few days earlier, he had seen Pandolph and Grando arguing. Grando slashed at Pandolpho with a knife that cut a hole in Pandolph’s “pantaloons.” Grando was quoted as saying, “Go away, or I’ll kill you.”

At this point, there’s little doubt that Carlo Grando is the murderer – but he hasn’t been seen since the night of the stabbing.

Arrested!

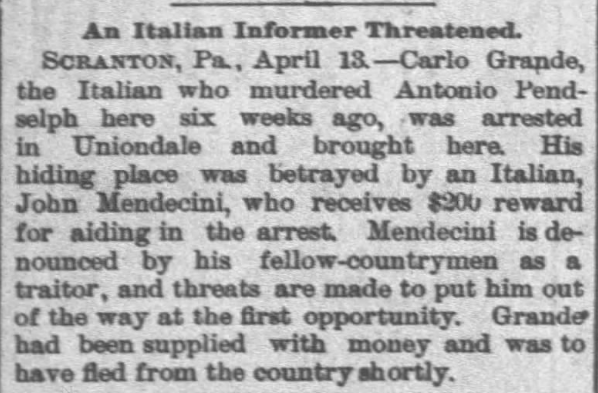

John Mendicino, who witnessed the slaying and was a long-time friend of Pandolph, learned that Grando’s friends were collecting money to help send the murderer back to Italy. Mendicino, however, was intent on stopping the man from escaping justice – and it didn’t hurt that there was a $200 reward for his arrest.

Mendicino tapped into his Italian network and learned where Grando was holed up. He pulled together a couple of men and tried to apprehend the murderer. When they got to the cabin where Grando was hiding, they were threatened with guns to back off. Several Italian railroad workers were helping to hide Grando until they could raise the money to help him escape back to Italy.

April 13, 1889

Mendicino reported the incident to authorities who then went in to capture Grando. Finally, on April 10, 1899, just over a month after the slaying, Carlo Grando was in custody in the Lackawanna County jail – and Mendicino received a $200 reward.

Sergeant Riley from the Scranton Police Department was credited with the arrest. He went undercover and worked with the Union Dale constable to secure his capture.

April 12, 1889

Riley said when he found Grando, the suspect gave little resistance and surrendered without incident. He did not have any weapons in his possession – only a few cents and a half dozen eggs.

It was learned that after Grando escaped the city, he made his way to his cousin’s home in Carbondale. From there, he went to Forest City, a known Italian enclave to be with friends. The men kept him moving to avoid capture. They moved him to Herrick Center and then finally to Union Dale, where he was captured.

The arrest happened just in time. Grando’s friends had just received their month’s wages the day before his capture. Investigators believed that if he had another day, he would have fled the country.

Grando was irate with Mendicino and called him a traitor. He swears that his fellow countrymen will exact revenge on the storekeeper who lived on Providence Road in Bull’s Head.

The Trial

On June 24, 1889, just six weeks after his capture, Carlo Grando was on trial for murder. The session opened up with the District Attorney reciting the law and insisting that this was murder in the first degree – that it was willful and premeditated.

June 26, 1889

The DA called several witnesses who had already testified at the Coroner’s inquest. They all reiterated the same story. There seemed to be little doubt that Grando was the man that was responsible for Pandolph’s death.

Grando’s defense attorney did nothing to combat their statements. No witnesses were called on his behalf and the defense rested. It did not look good for the defendant.

Grando got a bit of a break when Judge Connolly told the jury that based on the evidence, murder in the first degree could not be justified. He said it appeared like nothing more than a drunken fight that got out of hand and that if the jury were to find Grando guilty, it could only be manslaughter. With that, the case was turned over to the jury.

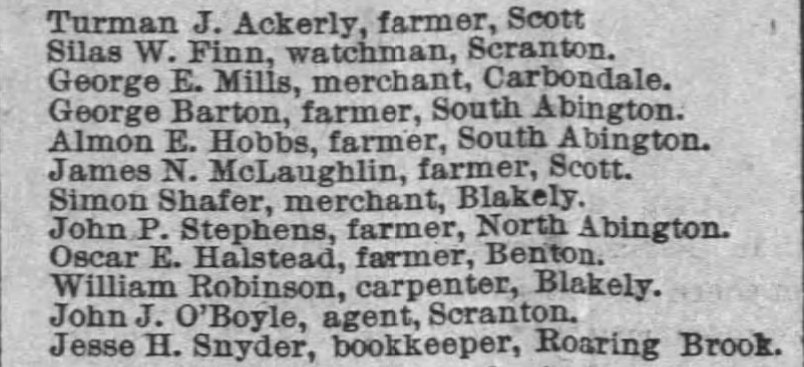

The Italian would be swiftly judged by a jury of his peers – without a single Italian immigrant on the jury.

June 26, 1889

After a very short absence, the jury came back with a verdict. Grando was guilty of manslaughter.

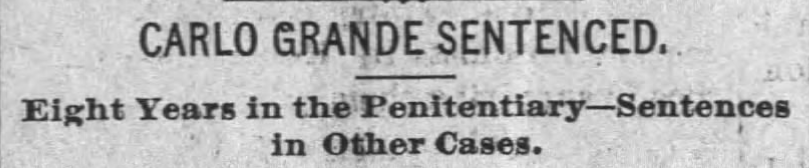

The Sentence

Three days later, on June 29, 1889, he was sentenced to eight years of “hard labor” in jail and a fine of $100 plus costs.

July 3, 1889

He would be transferred to the Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia on July 2, 1889, to start his sentence. He showed up with no possessions. No money. No jewelry.

In 1895, Grando was one of seventy-nine Lackawanna County convicts that were held at Eastern – each one costing Lackawanna County $0.18 per day ($65.70 per year). Of them, twelve were convicted of murder or manslaughter, including one woman, Melzene “Mel” Boughton of West Scranton who had stabbed her husband to death.

Feb 6, 1896

Release

Of his eight year term, Grando served six and a half years in prison. He was released from Eastern on December 31, 1895 – likely for good behavior.

Jan 1, 1896

Where Are They Now?

After his sentence, Carlo seemed to have fallen off the radar. I can’t find any instances of him back in Scranton. Where did he end up? Was he completely reformed? Did he return to his native country? We may never know.

The same with John Mendicino. I can’t find any record of him in Scranton after that. There was a John Mendicino, the same approximate age, who died at the age of 34 in New York in 1893 – just four years after Grando’s conviction. His death was recorded in a Scranton church. Was it the same man? How did he die?

First Presbyterian Church of Scranton

We do know that the Italian immigration to Scranton was just beginning to heat up. Hundreds, if not thousands of Italians would make their way to the Bull’s Head section of town over the next couple of decades. The drinking and violence in that part of town were notorious for decades.

Thankfully, things would eventually settle down and since then, the Italians have left a huge, and positive legacy on the city.