Dr. John D. Durkin was born in Ireland around 1819. During the 1855 census, he was listed as being 32 years old, and he lived with his wife, Mary (24), and two young men, M. Burke (14) and John Burke (9). The two boys were likely Mary’s brothers. All were listed as having immigrated to the United States in March 1855.

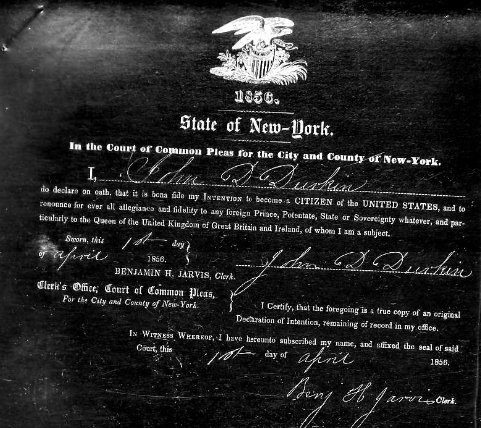

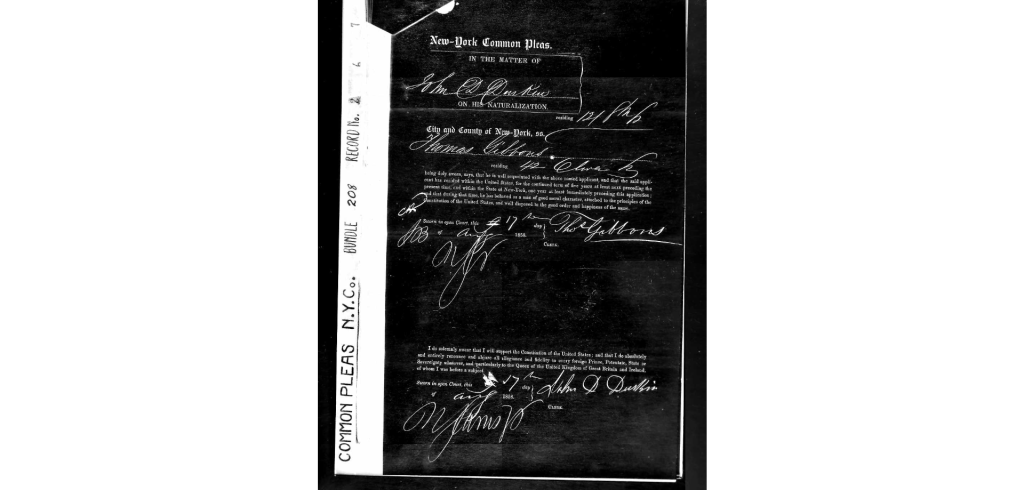

Dr. Durkin signed his Declaration of Intention to become an American citizen on April 1, 1856 – starting the process that would take years to complete.

April 1, 1856

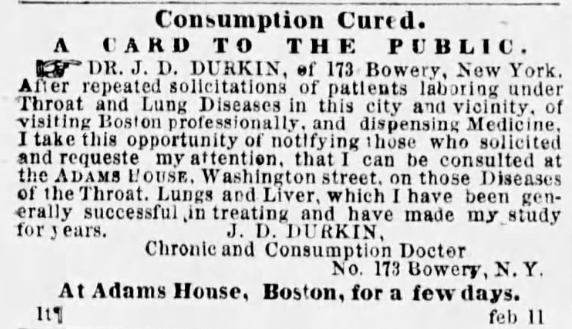

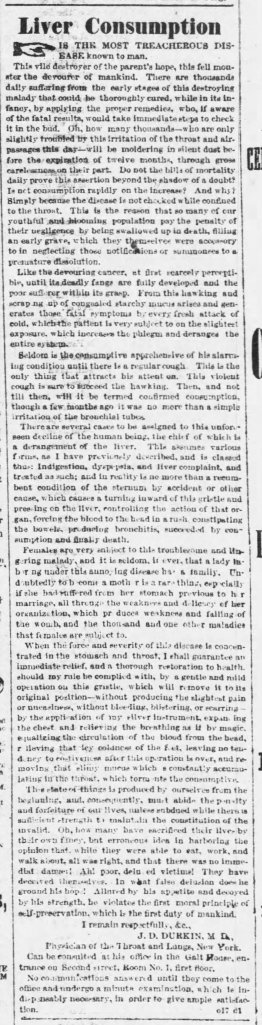

From his office on the lower-east side of Manhattan at 173 Bowery, he advertised his capabilities in different parts of the country. His specialty was treating throat and lung diseases, primarily Tuberculosis, then known as “consumption” because the disease appeared to “consume” the person through substantial weight loss.

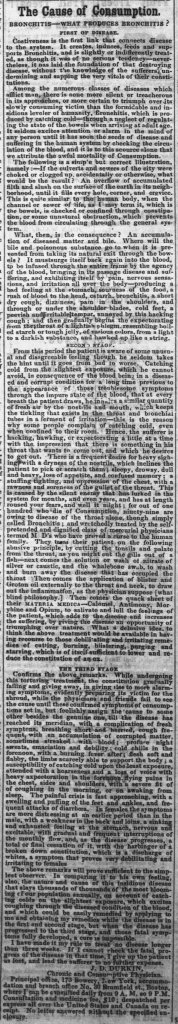

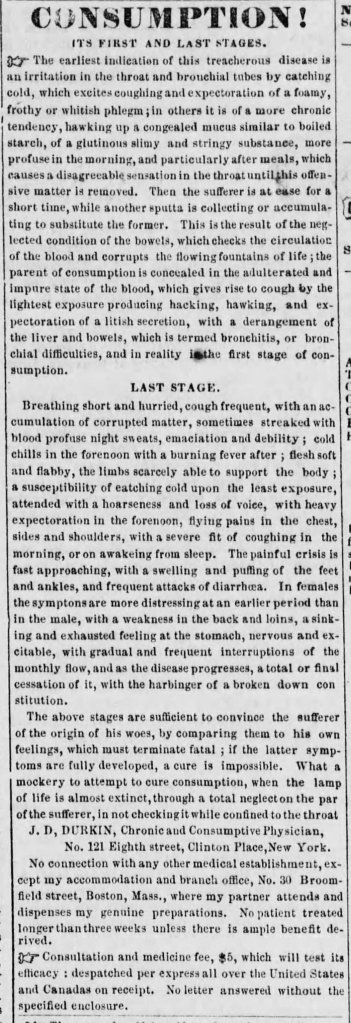

Durkin placed advertisements, many of which appeared as articles, in various newspapers that would promote his services.

February 11, 1857

From 1857 through 1860, his advertisements appeared in newspapers from (chronological order) Boston, MA (Feb-Mar 1857); Ellsworth, ME; Greenfield, MA; New York, NY; Montpelier and Vergennes, VT; Chicago, IL; Baltimore, MD; Reading, PA; and finally to Louisville, KY (Oct 1860).

March 30, 1857

He would travel to these locations to set up temporary facilities where he could see his patients – charging them $5 to $10 per session – equivalent to about $200-$400 today. Dr. Durkin and his partner preferred to establish their clinics in well-known hotels – like the Adams House in Boston (Feb-Mar 1857).

Boston, MA

Some columns would be more descriptive than others, but he would outline the symptoms of the diseases that had taken so many lives – telling people if they acted as soon as the earliest symptoms were identified, they stand a chance of survival with his medicine. If they caught the disease too late, they would surely die.

October 29, 1857

While still living in New York City, Durkin became a US Citizen on August 17, 1858.

Syracuse, New York

By the end of 1859, he left New York City permanently and moved to upstate New York. He was praised for purchasing a lot in the heart of Downtown Syracuse at the corner of Jefferson and Mulberry Streets (now State Street). At the time, Syracuse had a population of just 28,000 people. The Syracuse Daily Courier and Union was quoted as saying. “We rejoice, for the interest of our city, that such an enterprising man as Dr. Durkin has come among us. It is such men that are the life of a city and build up its prosperity.” They continued the praise with, “As a physician for the specialties he treats, he is one of the most successful in the country.”

His development plan included a three-story building with shops on the first floor and living spaces on the second, along with a hospital and room for his patients. The building would become known as the Durkin Block. His commitment to the city was lauded by the townspeople, and the building was scheduled to open by March 1860.

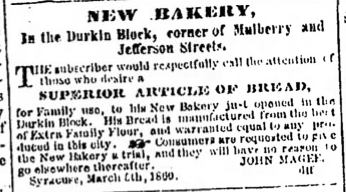

The Durkin Block became the home of a new grocery store and separate bakery, both run by John Magee. Magee lived at the same location and sold his “superior article of bread” on the first floor.

March 17, 1860

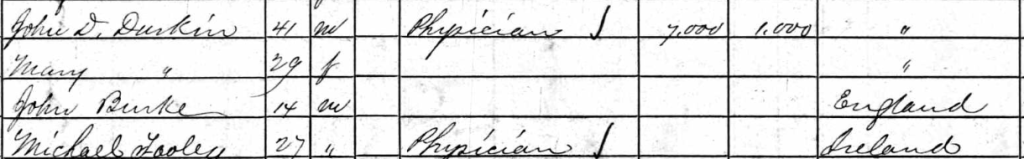

Durkin, along with his wife Mary, his business partner, Michael Tooley, and now 14-year-old boarder John Burke, lived together in the new building. There’s no mention of M Burke, who lived with the Durkins in New York City and would be 19 now.

Later, in October 1860, while still living in Syracuse, Durkin set up his temporary clinic in Louisville, Kentucky, in the now-historic Galt House. At forty years old, life in America seemed to be all good.

October 17, 1860

Turbulent Times

Before long, however, trouble set in. Less than two weeks after the battle at Fort Sumter that started the Civil War, the Durkin building caught fire on the evening of April 24, 1861. The building was heavily damaged but survived.

The fire was ruled suspicious, and investigators arrested Durkin, charging him with arson. They claimed the property was heavily mortgaged and that Durkin had a penchant for collecting a ”large quantity of personal property of the most costly character.” However, lacking evidence, the Grand Jury did not indict him, and he was released.

While he was free, the investigation continued. Shortly after his release, it was determined that Durkin had submitted an insurance claim for the personal property that he claimed was lost in the fire. But it didn’t take long for investigators to learn that the property was not lost in the fire and, instead, was stored in several different locations.

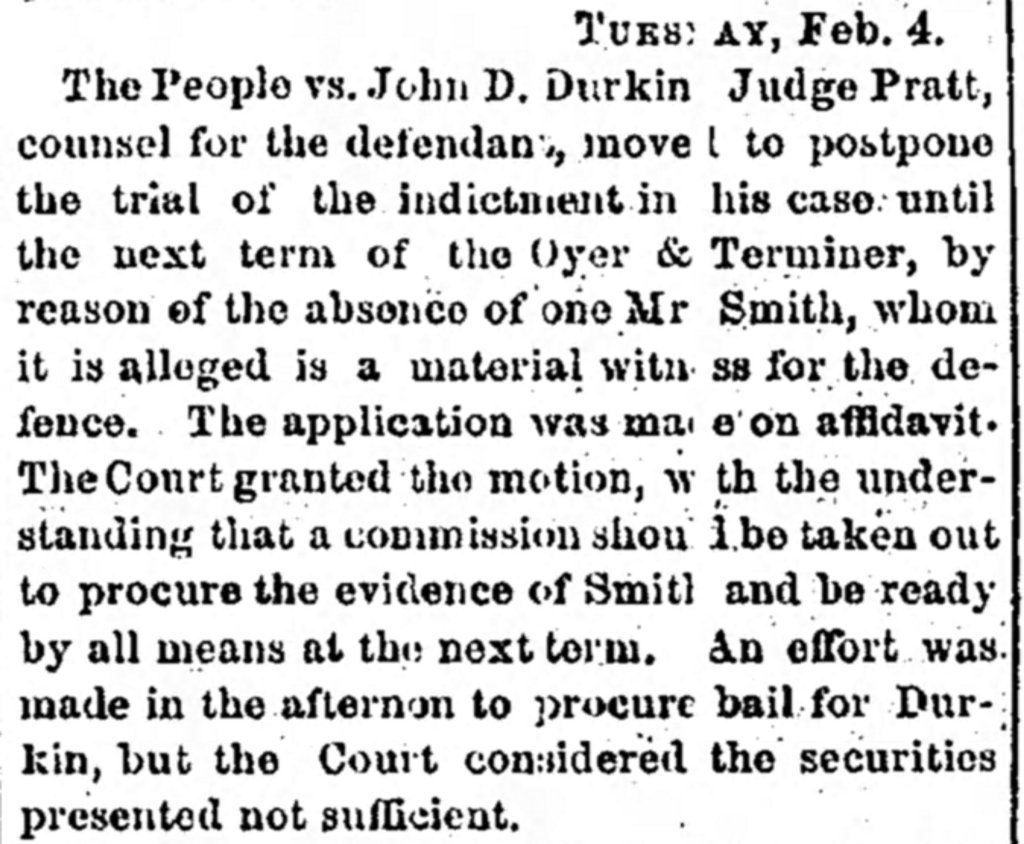

Durkin fled the city but was ultimately apprehended in Detroit to be brought back to Syracuse to face justice.

February 6, 1862

While still awaiting trial for his arson charges, in May 1862, Durkin was being sued by Amos J Williamson. While I can’t confirm the details or disposition of this case, there was an “Amos J Williamson” who owned the New York Dispatch newspaper. My assumption is that Dr. Durkin might have skipped out on payments to the newspaper.

May 28, 1862

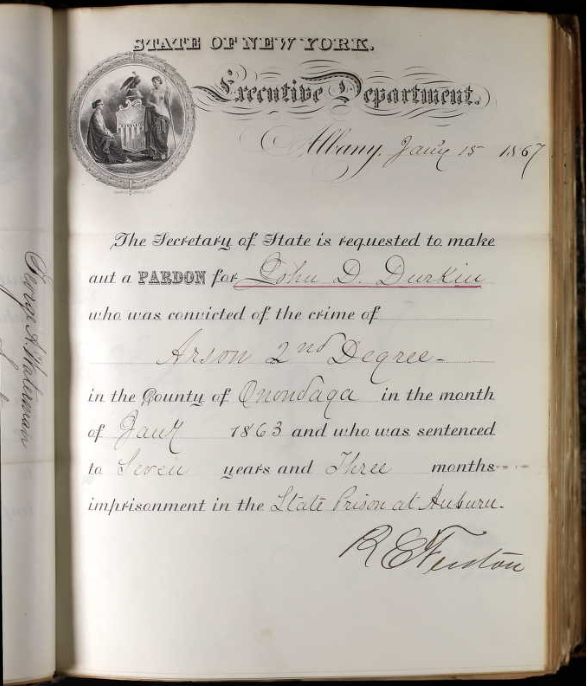

After several months of postponements, on June 6, 1862, Durkin was found guilty of arson and sentenced to seven years and three months in prison.

June 9, 1862

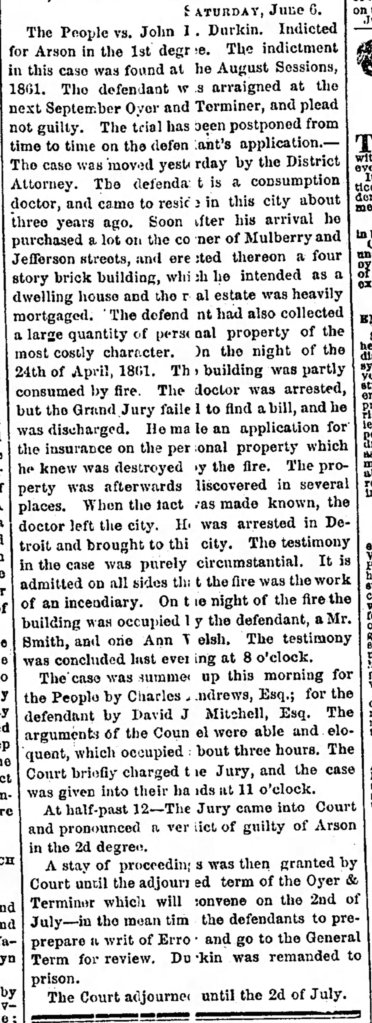

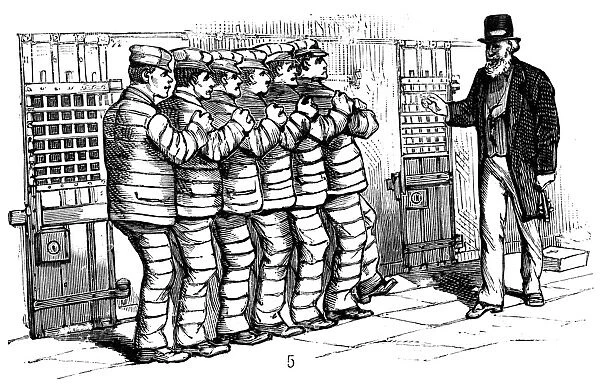

He was sent to the Auburn State Prison to serve his term. There, he was one of over 500 prisoners in the facility – which became famous for the “Auburn System” of incarceration.

In this system, prisoners were allowed to work together during the day but put in solitary confinement in the evenings. They were to remain silent 24 hours per day. They would wear striped uniforms and march in lock-step when moving around the facility. This was intended to break down the inmate’s individuality.

The “Auburn System” was viewed as a more humane imprisonment compared to the “Pennsylvania System,” which kept prisoners separated 24 hours per day.

There’s no firm evidence of what happened to Mary, Michael Tooley, or John Burke after Durkin was sent to prison. I did find that there was a “Mary Durkin”, same age, who was admitted to the New York City Almshouse on July 30, 1861. Her stay lasted only four days. It’s likely that this was her and that she left John after the fire and moved back to New York City. At the time, almshouses. were homes for the poor, disabled, or elderly and were largely funded by charitable organizations like churches.

Return to Practice

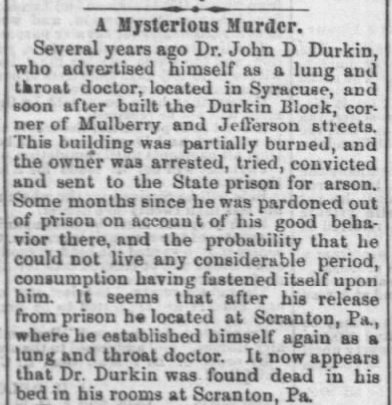

Finally, on January 15, 1867, Durkin received a pardon. After serving four years in prison, he was again a free man.

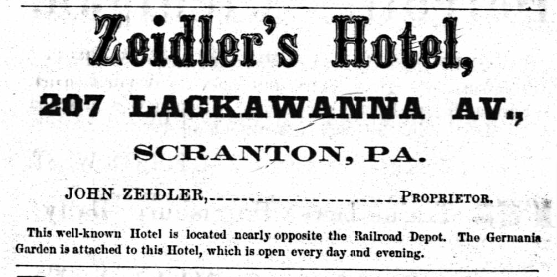

Dr. Durkin is back in business but seemingly alone, and he’s been in Scranton, PA, for about three months. He was reported to have had a suite of rooms and an office in John Zeidler’s new hotel, located at 207 Lackawanna Ave in downtown Scranton. Patients were lining up to see him again.

The doctor traveled to Wilkes-Barre for a 4-day trip, where he worked out of the home of Dr. Martin Bauer. He returned to Scranton late Tuesday evening, May 28th, 1867. He arrived back at the hotel with another man. When he picked up a key from the front desk, he chatted with Zeidler and said that he had so much business that he needed to get a helper.

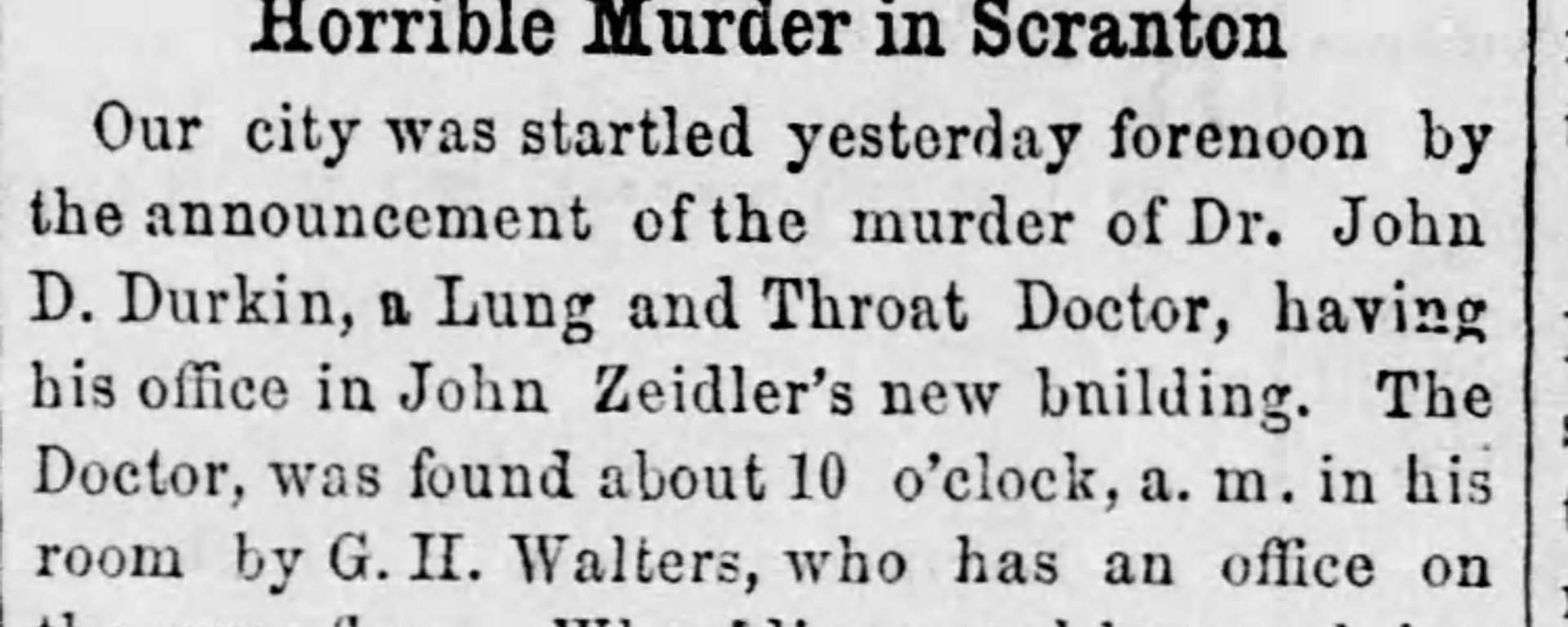

Murder!

On the morning of May 29, 1867, patients were once again lined up to see Dr. Durkin. With several sitting in the waiting area, they asked a neighboring tenant if he knew of the doctor’s whereabouts.

The neighbor, George H. Walters, whose Emigration and Insurance office was next to Durkin’s, took it upon himself to enter Durkin’s room. There, he found the doctor lying on the floor, stiff and cold, with a small amount of blood pooling near his head.

Durkin was dressed for bed, his cane lying at his side. The initial thought was that it was an accident – that he fell and hit his head.

Speculation quickly arose when the doctor, who was known to carry a lot of money, was found with only four cents. It was believed that he also wore a watch, but there was none to be found. The Coroner called together a jury, and he requested an autopsy be performed.

The Investigation

The autopsy revealed that Durkin had several minor bruises on his body – most of which would not be considered lethal. The exception is a contusion on the back of his head. It was believed that this wound was the result of a lethal blow.

Small pieces of rock were found within the wound, and investigators found a small, 3 or 4-pound rock near his bed at the hotel.

Further examination of the body revealed two broken ribs and a slight wound on the temple – but these could have been from the fall to the floor.

Zeidler told investigators that he saw a stranger with Dr. Durkin the night before and provided a description.

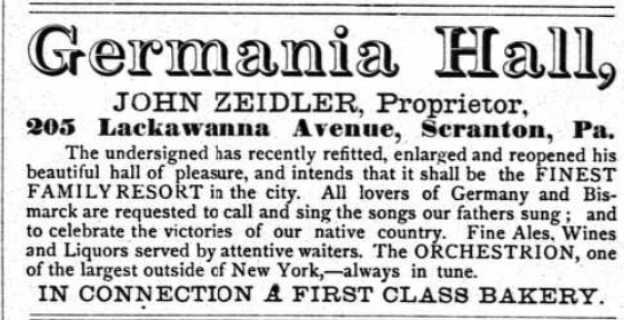

The hotelkeeper, who also owns the Germania Hall next door, told investigators that he himself had locked the doors that evening, leading investigators to believe that the murdered had either a) already been in the building when the door was locked, b) had a key to gain entry, or c) entered through a window on the lower floors before going up to Durkin’s room.

Zeidler’s children slept in a room next to Durkin’s. They claimed they heard a voice in the night call out, “Murder!” but they were too frightened to do or say anything.

The Search

Zeidler also tried to find out where the man had slept the night of the murder but wasn’t able to determine it based on his contacts throughout the city.

The suspect is described as being “5’7″-5’8″, very slenderly built, light hair and complexion, light sandy whiskers, and is an Englishman.”

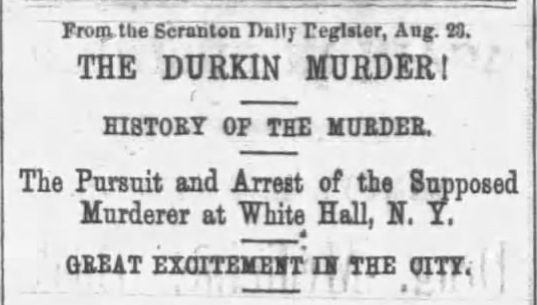

News of the cold-blooded murder spread quickly, with reports showing up in newspapers as far away as Kansas – but still, the murderer was on the loose.

June 11, 1867

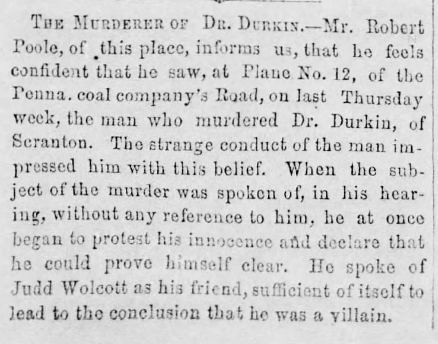

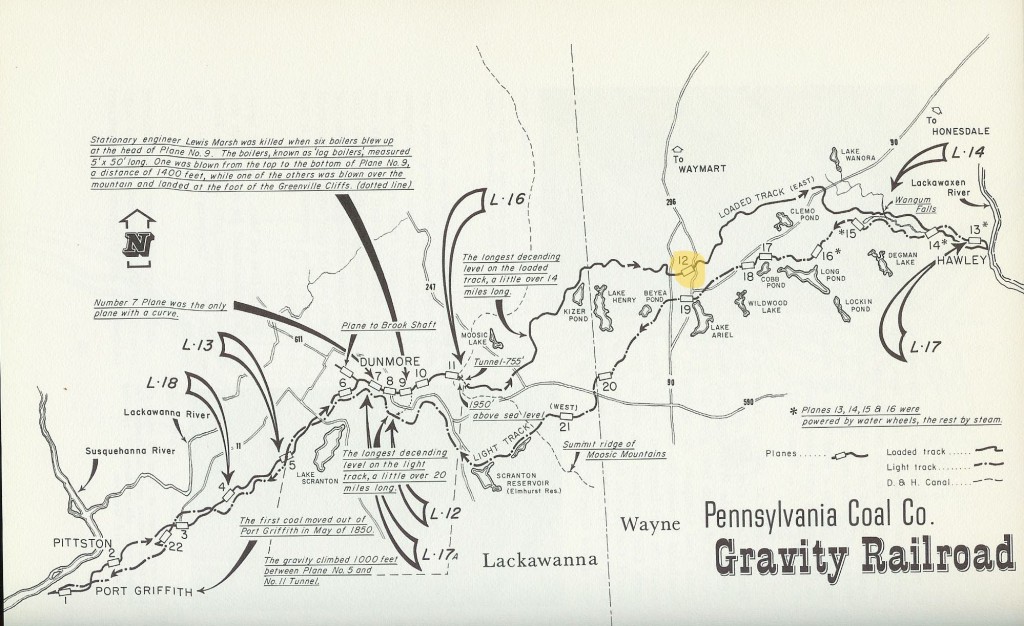

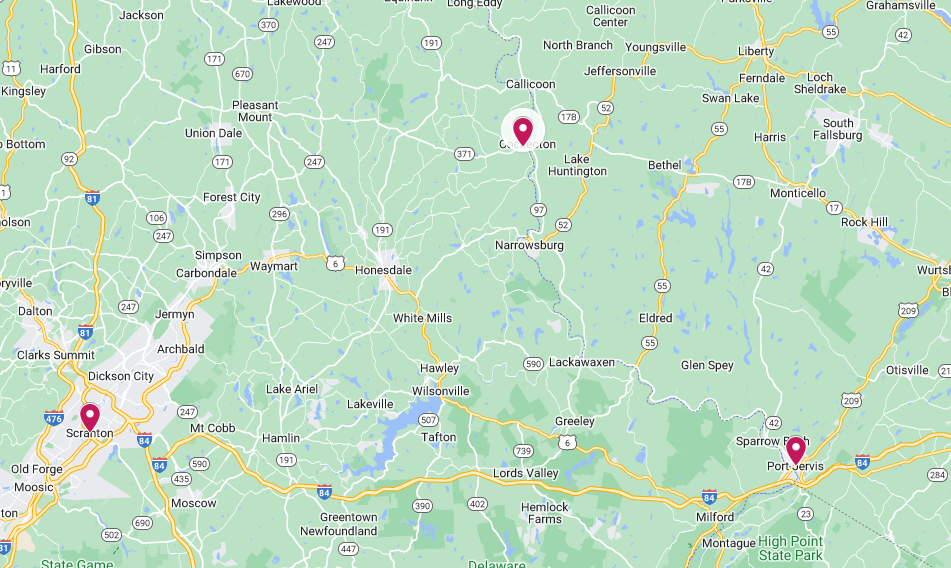

Another lead came when a witness claimed to have seen the man responsible for the murder along the railroad tracks at Plane #12 out by Lake Ariel.

June 13, 1867

Robert Poole told police that when he saw the suspicious-looking man, he immediately began professing his innocence and said that he had an alibi to prove that he didn’t kill the doctor. Oddly, the man proclaimed he was friends with another notorious local villain, Judd Wolcott. Why he would admit to that yet profess his innocence is curious.

Courtesy: Bill Buckland

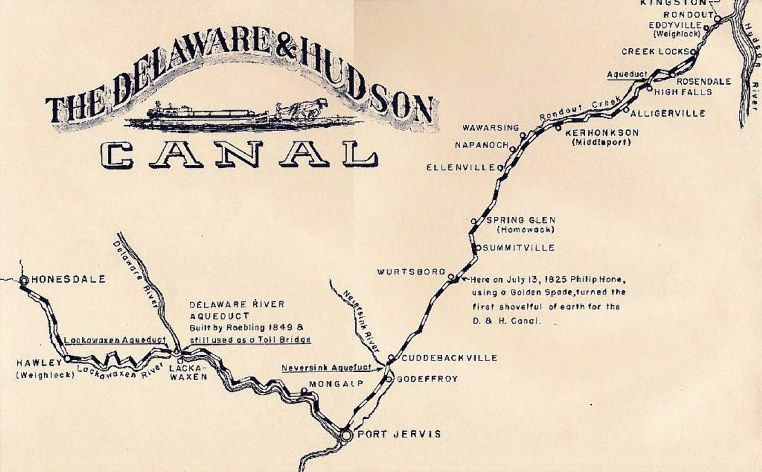

Following up on that lead, three weeks after Durkin’s death, Scranton authorities, along with Port Jervis police, were still in pursuit of the suspect. They tracked him north, past Port Jervis. They believe he was following the tow tracks of the Delaware & Hudson Canal. The trail grows cold, and they call off the search, returning to Port Jervis.

Now, in mid-July 1867, there are reports of a suspicious man seen lurking around the wooded area of Damascus, PA, a remote area northeast of Scranton and Northwest of Port Jervis.

The man is said to hide during the day but enter farmhouses and barns in the evening to secure his provisions. A witness found him sleeping one day and shared his description with investigators. Police believe it’s a match to their suspect. They surrounded a swampy area and were said to have hemmed the man in, and his capture was imminent.

The suspect once again slipped through the net. Days passed by with no additional reports or sightings – until.

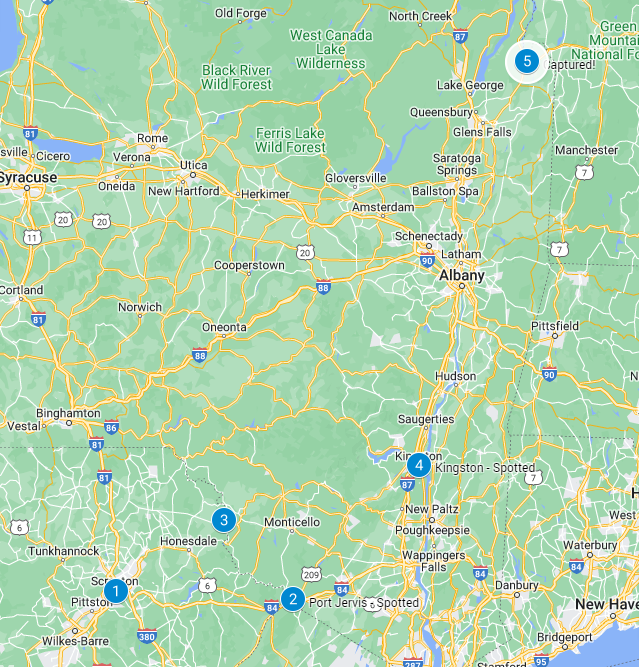

A man visited the jail in Kingston, NY, to see his brother, who was being sent to the state penitentiary the next day. Authorities sent a telegraph to Scranton with the description of the man. For some reason, the response was delayed. When it was finally confirmed that it was a match, it was too late. The visitor had left the scene, but the police had their next clue.

Captured!

Finally, Lorenz Zeidler, brother of John Zeidler, who was credited with much of the manhunt, tracked the man from Kingston north. up past Albany and into the Lake George area of upstate New York along the Vermont border, to a town called Whitehall.

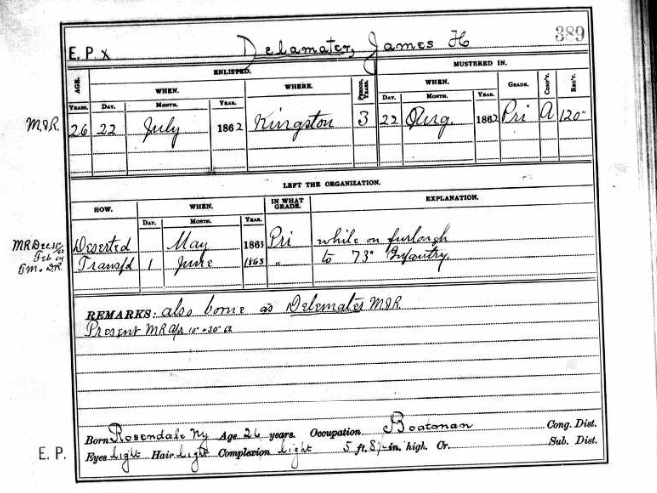

James H. Delamater, aka Delemater, was born in Rosendale, New York, near Kingston. He was about 32 years old when he surrendered without incident and was transported back to Scranton. Along the way, he continues to proclaim his innocence.

Delamater was no stranger to running. He deserted his regiment while serving with the 120th NY Infantry in the Civil War while he was on furlough. He was ultimately returned to service with the 73rd NY Infantry.

Back in Scranton, the crowd of people cheered as the train pulled into the station with the man believed to have committed this brutal murder and robbery. As soon as Zeidler saw the man, he confirmed that this was the same man he had seen with the doctor the night before the murder.

August 24, 1867

He was brought back to Zeidler’s Hotel before they transferred him to the Wilkes-Barre jail. While at the hotel, Zeidler brought him in to Dr. Durkin’s room. When the man saw the dried blood on the floor, he blurted out, “Holy Jesus Christ.”

Preliminary Trial

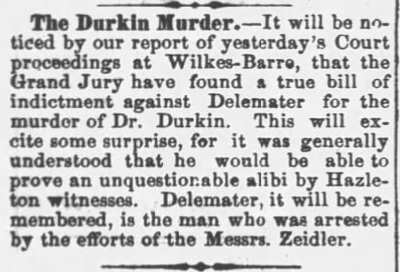

Even though investigators had who they believed to be the killer, there were still some who speculated that Delameter was innocent – and that he had witnesses that could attest to his whereabouts on the evening in question.

The Trial

Typical of the time and in accordance with the Sixth Amendment, they upheld the defendant’s “right to a speedy and public trial.” Starting on Friday, January 24, 1868, the prosecution, led by a young District Attorney Woodward, called several witnesses who placed Delamater at the scene of the murder – none, however, were eyewitnesses to the actual murder.

January 25, 1868

E.G. Snover said he saw the man at the Zeidler’s bar on the night in question. He knew it was the same man because Delamater, after he spilled Snover’s beer, gave him a nasty smirk. He saw that same nasty smirk when Delamater returned on the train.

Charles Schott, a barber in Hawley, testified that he gave the suspect a shave late in the day after Durkin was killed. About a week later, he saw the same man on the bank of the river. At that point, the man asked the barber what he would pay him if he jumped into the Lackawaxen River and drowned himself. Schott offered up a penny, and the man said he’d hold out for a better offer.

John Otto testified that he saw Delamater in the barbershop in Hawley. He claimed the man was either drunk or crazy. He hadn’t seen the man prior or since that one time – until today.

George Lewis, a baggage man for the railroad, saw the same man in Zeidler’s bar the evening of the murder. The man gave a stare at Lewis that was concerning – that’s why he remembered him.

Charles Shelp, a Hawley resident, saw the man around Hawley the day after the murder. He said he was a boatman who missed his boat and wanted to join another. Shelp said boating season opened in May and that 50-60 boats per day would pass through the area on their way to and from Honesdale, making it a great place to look for work.

Elias Schleezer, a grocer in Hawley, said he met the man a day or two after the murder. He appeared drunk and was asking for more whiskey. He was also looking for a place to stay. Schleezer offered neither.

S. Bristol, an innkeeper in Hawley, said that he rented a room from him. When registering, he gave his name as J.H. Stratford of Ulster County, NY.

Warren L Pearce also testified. He used to live in Ulster County, NY and acted as their constable for seven years. Pearce says he has known the defendant for 10 or 12 years and knows him as James Delamater from Ulster County, NY. He says Delamater’s parents live in Ulster County. He also says that he knows John Stratford from Ulster County, but the man on the stand is not Stratford.

Pearce added that he saw Delamater on June 6th when he came into Court in Ulster County. The defendant invited a few of the courtroom workers out for drinks. While out, he wanted to know if there was any way they could help to keep his brother from going to the State prison – and he was willing to pay. He offered up to $500 if they could help.

Delamater flashed the money, prompting Pearce to ask where he was able to come up with so much money. Delamater told him he was working in Scranton building a dock for $8 per day, and he saved his money to help his brother.

Delamater also asked Pearce if he had heard anything about a doctor who was robbed and murdered in Scranton. When Pearce said he was unaware, Delamater told him that they were looking for a man they called “Buckshot.”

Margaret Van Steenburgh, Delamater’s aunt, took the stand and testified that James visited Kingston, NY, at the beginning of June 1867 and stayed at her house. She went to visit her other nephew at the jail with her daughter, James, and his mother. On the way, they stopped to buy some tobacco and other things for the prisoner. She claimed James had a stack of cash – and told her that he had more than $800. On the trip, James also bought dresses and other items for his mother and his aunt.

She said James told them that the police were after him, but he escaped a couple of times. He told them of his time in Hawley, then Port Jervis, then to the woods near Damascus. He told them that if anyone came looking for him to not say anything.

Van Steensburgh said that James had married his wife in Pennsylvania, but in 1866, they lived in Rondout, a village on the Hudson that is now part of Kingston. They stayed there for a couple of months before moving back to Pennsylvania.

Polly Schoonmaker, daughter of Margaret Van Steenburg, testified that she had seen Delamater recently in Kingston, NY, but hadn’t seen him since today.

Leonard Sirrine testified that as a constable for Ulster County, NY, he knew Delamater. He also knows Stratford and believes the two men know each other since they lived in the same area at the same time.

Lorenz Zeidler, the hotelier’s brother, saw Delamater in Whitehall, Washington County, NY. He was there to arrest him. At the time, the defendant was working in a sawmill under the assumed name of James Dockerty. Under questioning, “Dockerty” maintained his innocence and said he didn’t even know where Scranton was located – but he was familiar with Hazleton and Wilkes-Barre.

Zeidler told the jury that Delamater made several incriminating statements when he was apprehended, including asking Zeidler how he found him “about 50 times.” Zeidler said it took time, money, and trouble.

Finally, the most damning evidence came from Edward Weiswell, an 18-year-old from Whitehall. He told the jury that he worked with the man on trial but that the man claimed his name to be Dockerty. The men worked together for about a month at a brickyard in Whitehall. Initially, Weiswell thought the man was very wealthy because of his style, the way he talked, and the way he acted, but it was later revealed that he was just a regular laborer.

One day, while the two were working alone, the man told Weiswell that he had killed someone. When Weiswell questioned him about it, he said it was a doctor from Pennsylvania and that he stole about $800 from the man.

With that testimony, the Commonwealth rested its case.

January 27, 1868

The Defense

Delamater’s attorneys made a convincing argument. They claimed the vast majority of the prosecution’s testimony was circumstantial and hearsay – and no one witnessed the actual murder of Dr. Durkin. Their strategy was to sow enough doubt that the jury, without the benefit of witnesses, would have a difficult time convicting someone of murder. Their primary tactic was to have witnesses testify to James’ whereabouts on the evening of the murder on May 28, 1867.

They opened by calling Emanuel Rymiller of Hazleton. He testified that he knew James Delamater from working in the mines from April 1867 until about June 1, 1867 – a time span that included the day of the murder. James would load the cars with coal for $2 per day while living with Mrs. Dice.

Another mine worker, John E. Lobb, was called. He said that he worked with Delamater from the same timeframe at the Pardee & Co mine. He said that Delamater worked every day in May except for the 30th, which was Ascension Thursday. This would put Delamater in Hazleton at the time of the murder – and making the trip back and forth would be nearly impossible given the timeline.

Hugh Gallagher was sworn in. He, too, was a miner and testified to the same points – that Delamater worked from April through June 1, missing only May 30th, with his last day, June 1st. This means that Delamater stuck around and worked even after he allegedly killed Dr. Durkin.

Elizabeth Dice, a widow with whom Delamater roomed, testified that she took him in during April and that he stayed with her until June 3rd. There were two other boarders in the home, Frank Darrin and James Mallory.

She added that, at one point, James gave her $10 to hold for him. She hid the money with hers. When he asked for it back, Elizabeth took out the combined savings, which was about $135, and James took all of it – even Elizabeth’s portion. Elizabeth thought it was a joke, but he kept all $135. It was the last time Elizabeth had seen James – before today. This was the Defense’s way of showing that James had a lot of cash at his disposal.

Elizabeth, under cross-examination, testified that Delamater showed up and said he was a single man. During his stay, told her that he loved her and promised to marry her – frequently kissing her. Later in the relationship, Elizabeth found out that James was married, and she told him to go back home to his wife. James recommitted his love to her. He said he would work “until his arms fell off” to make enough money so he could get a divorce and live with Elizabeth.

John and Frank Barton were called. They are paymasters for Pardee & Co. The men testified that Delamater worked April through June 1. Delamater asked for his final payment on June 1, but the men made him wait until Monday, June 3, 1867, to collect his final payment.

After some rebuttal, the Defense rested on Saturday afternoon and all were released until Monday.

On Monday morning, closing arguments were heard and by Tuesday at noon, the case was handed over to the Jury. Following the closing arguments, the Pittston Gazette said that Delamater’s attorney, H.W. Palmer, gave “one of the most eloquent and effective arguments” they had ever heard.

By 6:00pm on Tuesday, the jury was still not able to reach a verdict. The vote stood at 9 for conviction and 3 for acquittal. They were given supper and told that they would receive two meals per day until they could come to a consensus.

The Verdict is In!

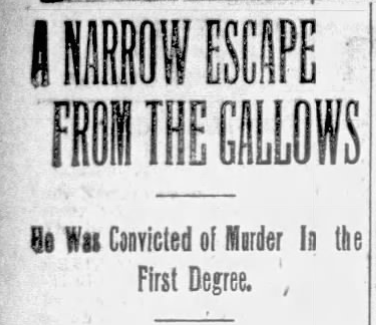

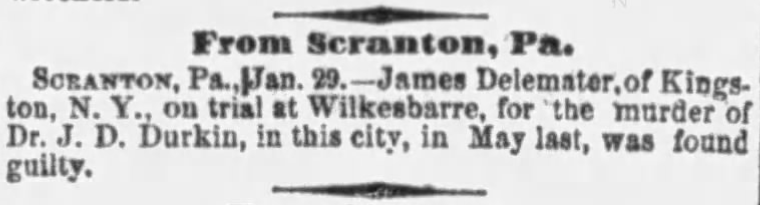

On Wednesday, the jury found Delamater guilty of murder! But it wasn’t without controversy. Many believe that Delamater was innocent and that the investigators jumped the gun on identifying him as the prime suspect. Regardless, the news spread quickly and was reported throughout the region.

January 30, 1868

January 30, 1868

January 30, 1868

Delamater’s defense immediately filed a motion for an “arrest of judgment” and asked for a new trial. A month later, Attorney Palmer would be granted his reqest.

Retrial

At the new trial, just three months later, on April 29, 1868, a new jury was impaneled, but there was no one from the prosecution present. The jury, at the request of the court, found Delamater not guilty and acquitted him of the charges.

May 20, 1868

Judge Conyngham was quoted as saying, “James Delamater, you were convicted at the last term of the sessions for murder. It would seem that the verdict was founded upon your own foolish talk and boasting. The jury must have given great weight to this testimony of the boy to whom you so foolishly boasted. You certainly acted very discreditably toward the woman living in Hazleton from whom you took the money.” He continued, “You have been incarcerated in the county jail for a period of nine months and came very near to being hung, were it not for the interference of the court in granting you a new trial. It appears there is no one appearing against you who desires to prosecute this matter further; therefore, under the circumstances of the case, you are entitled to be discharged by the court.”

The Judge encouraged him to “go out of this courtroom a better man than when you first came here.”

And with that, the shackles were ordered to be released and James was a free man.

Reaction

Almost immediately, there was outrage and a demand for answers as to why the man was convicted in the first place. It seems that many were questioning the legal system and wondering if there was an ulterior motive behind the false accusations.

May 9, 1868

Life After Charges

Details are sketchy after his release from prison. I can’t find him in the 1870 census and his name does not appear in any newspaper articles. It was reported that James had moved away from the area – perhaps to escape the attention.

He pops up in the 1880 census, now 47 and living in Kingston, PA, with his wife, Elizabeth, 37, and daughter, Elisa, 9. It’s likely that Elizabeth is Elizabeth Dice, with whom he boarded when the murder of Dr. Durkin occurred.

In August 1892, James was living in Ashley, Luzerne County. He brought a case against a woman and her son for assault and threats, but the case was dismissed.

In October 1897, James, still a miner at 63 years old, spoke at a meeting to discuss forming a union. He spoke about “dockage robbery”, a term used to describe how the bosses would underpay the miners for their work.

By April 1899, times seemed to be difficult for James as he approached his 65th year. He successfully petitioned the court to relieve him of his tax debt due to poor health and inability to work. He claimed he has a large family to support and lists only a single “little daughter” who is employed.

Perhaps the financial difficulties were taking a toll on him. A month after that, in May 1899, he was arrested for assault and battery against his wife and two daughters.

Another month later, in June 1899, James was accused of taking a pan of coal oil and lighting it on fire in the family’s home. He left the home and let the fire burn until firefighters extinguished the blaze. He was arrested and faced charges of arson. Things were spiraling down for James.

June 30, 1899

A Bombshell!

All hell broke loose when, on September 23, 1899, Elizabeth was in court to support her claim of desertion against James. She claimed that James threatened to kill her before he kicked her out of the house and then refused to provide any level of support.

Judge Woodward heard her testimony – but was about to be blown away by what came next.

Elizabeth was growing more agitated by having to relive the situation. She claimed that James was a troublesome man with a vicious temper to which James countered to the contrary. Suddenly, Elizabeth stood up, pointed a finger at her husband, and screamed, “Who killed Dr. Durkin!?” Without hesitation, she followed up her rhetorical question by saying, ” You did. You are a bad man.”

“Who killed Dr. Durkin!? You did. You are a bad man.”

Elizabeth Delamater

She then turned to the Judge and said, “I was good enough for him then, Judge when I walked as far as Hazleton to get witnesses to help him in his case.”

The confused Judge then recalled the situation in which he was all too familiar. Judge Woodward flashed back to 1867, some thirty years ago, when he was a young District Attorney in Luzerne County. He was tasked with prosecuting a man named Delamater for the murder of Dr. Durkin.

Woodward asked James where his brother was, thinking the man who murdered Dr. Durkin wasn’t the same person sitting in front of him. Then, James stood up and said, “I am the man, but I was acquitted.”

The Judge, stunned by what had just occurred, sat quietly for a bit until he told the two to go home and work things out. He issued a continuance to allow time for the couple to reconcile. He didn’t want to separate them because he knew, given James’ advanced age, they only had a few years to be together. Releasing them, he said, “God will separate you soon enough.”

September 24, 1899

Family Troubles Continue

Less than two months later, in November 1899, the Delamaters were back in court. They couldn’t come to an amicable agreement, and this time, Elizabeth showed up with two of their daughters.

During testimony, James said he could not work due to his age and health reasons and, therefore, couldn’t afford to pay any support. Elizabeth claimed that James was living in the house with another woman. James fired back at Elizabeth and charged her with everything she was accusing him of.

One of the daughters interrupted the court and said she wouldn’t trust him, even if he was under oath. She pointed out that he swore allegiance to his country during the Civil War but ran away from his regiment.

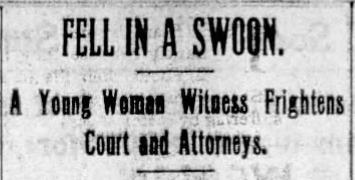

The arguments were highly contentious – to the point that one of the daughters ultimately fainted in the courtroom. The other daughter broke down in tears. As she fell to her knees, she begged the Judge to do something to stop the disgrace of her family and end the arguments between her parents.

The Judge ordered Elizabeth and the girls to return home and to live in half of the house while the parents tried, once again, to reconcile.

Escapades Continue

In July 1903, residents throughout the area along the Susquehanna River bank near Market and River Streets were shaken when an explosion echoed through the area. The people rushed to the scene. expecting to see the bridge blown up. Instead, they found James sitting along the bank, fishing pole in hand, with a sign of bewilderment in his eyes.

When asked about the explosion, he said he found a power nearby with a fuse sticking out of the pile. Curious and thinking he could scare some boys who were nearby, he lit the fuse. Before he could escape, the pile exploded. He thought he had died but was spared any serious injuries. He said, “Don’t tell me I was a darn fool. I know it, and you can put it down that I will, after this, steer clear of powder near the river.”

Many thought the story sounded “fishy,” believing he was using the powder to aid in his fishing, but officials couldn’t prove he had any ill intent, and no charges were filed.

July 23, 1903

Another Fire

James was back in the news again later in 1903 when, in October, yet another fire was reported at the Delamater’s home on Hartford Street.

October 12, 1903

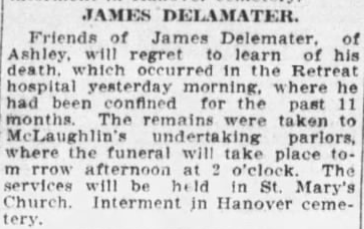

James’ story ends when he passed away at the age of 73 while in the Retreat Hospital in Newport, Luzerne County. No family is listed in his death announcement.

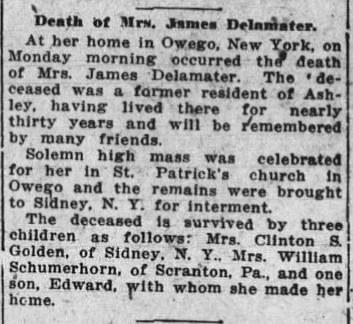

Elizabeth moved to Owego, NY, to live near her son Edward. She passed away in 1915 at the age of 70. Her obituary lists two daughters along with her son Edward, but the names of the daughters can not be ascertained. One is listed as Mrs. Clinton S. Golden, and the other as either Amy Foster or Mrs. William Schumerhorn.

February 10, 1915

February 13, 1915

Summary

Dr. Durkin’s life was one of the highest of highs and the lowest of lows. He enjoyed a lifestyle that only a few could imagine in the early days of America. He was traveling around the country, staying in the finest accommodations while enjoying the finer things in life. Was his cure really working? We may never know. Regardless, that lifestyle caught up with him when the Civil War broke out. He was overextended, and his world came crashing down on him. He spends time in jail, and his wife leaves him. Undeterred, he builds his practice back up and begins life anew. This time, his success leads directly to his death.

Meanwhile, James Delamater’s life was much like every other immigrant in America who had to toil away in the mines just to try to make ends meet. He struggled to keep a family together and likely moved to Pennsylvania to work in the mines to earn a living while his wife stayed behind to tend to their family. If he did kill Dr. Durkin, which I believe he did, was it intentional? Or was he just trying to take his money to raise his family?

So, what do you think? Did James Delamater kill Dr. Durkin? Did the prosecution present enough circumstantial evidence to convince you? Or does the lack of an eyewitness to the murder justify his acquittal? Would the prosecution have secured a conviction if they went for a lesser charge? Why didn’t the prosecution show up for the second trial? Were they not convinced that James killed Dr. Durkin? Does Elizabeth’s courtroom outburst change your mind? Do you think Judge Woodward was second-guessing his decision to not show up for the second trial after Elizabeth’s outburst? So many questions.